What a powerhouse of a piece. This is new and uses all types of immersive techniques to tell this compelling story. The combination of illustrations merges with 360 images, tiny planets, VR and parallax storytelling sets a new, high bar.

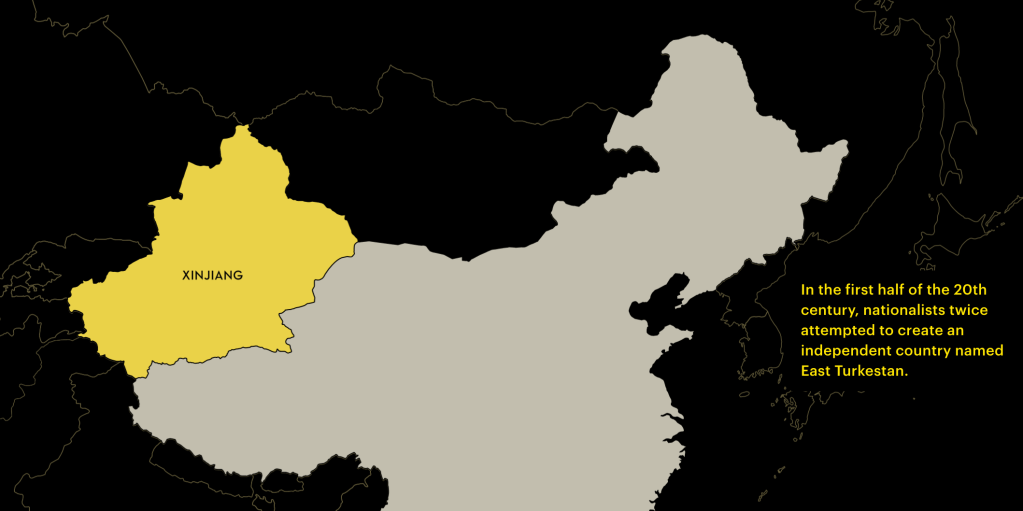

Since 2016, authorities in Xinjiang, China have implemented one of the most advanced police states in the world. By 2018, as many as a million people were held in a vast network of “reeducation” centers. Officials used broad pretexts to justify the detentions, including travelling abroad and owning a prayer rug. It is likely the largest mass-internment drive of ethnic and religious minorities since the Second World War. “Reeducated” is a two-part project by The New Yorker covering this human rights crisis, including our first virtual-reality documentary of the same name and an immersive interactive, “Inside Xinjiang’s Prison State.”

The virtual-reality documentary takes viewers inside one of Xinjiang’s “reeducation” camps, guided by the recollections of three men who were imprisoned together at the same facility. Using hours of firsthand testimony and hand-drawn animation, the V.R. film reconstructs the experience of detention and political reeducation in an immersive three-dimensional space.

“Nobody interrogated me. Nobody told me what was happening,” said Erbaqyt Otarbai, a truck driver who was detained after saving religious videos on WhatsApp. Inside the detention centers, prisoners spent ten hours a day in classrooms—studying Chinese or taking classes focussed on political indoctrination and the dangers of Islam—and some endured torture and stints in solitary confinement.

Our immersive interactive expands the scope of the film and puts those scenes within the context of the larger campaign of persecution against Turkic and Muslim minorities. The interactive helps readers visualize the securitization changes that occurred in locations throughout Xinjiang, where, in recent years, surveillance cameras and police checkpoints have become ubiquitous tools for authorities to track minority populations and suppress expressions of minority culture. Specific tactics include interrogation, the use of live-in cadres, forced confessions, and show trials.

While Nurlan Kokteubai, a retired math teacher, was detained in a “reeducation” camp, Communist Party cadres were sent to live with his wife, Aynur, as part of China’s Becoming Family program. The initiative has placed more than a million civil servants in the homes of Turkic and Muslim families in order to monitor and assess them. Former residents of Xinjiang also described police officers barging into homes, collecting prayer rugs, Quarans, and works of Kazakh literature. In December 2019, authorities claimed that detainees of the camps had “graduated.” However, our reporting shows that many were sentenced to long prison terms or forced labor instead.

The interactive uses pioneering, browser-based techniques to move readers through 360-degree scenes, guided by the commentary of our reporter, Ben Mauk. Similar to the film, the interactive also uses hand-drawn pen-and-brush animation, which allows us to go beyond the bounds of traditional photography and video to convey the emotional experiences of survivors.